Week 2 Applications

by Kevin Peter He, Brandon Roots, Phil Caridi, Sam Heckle, Akshita Bawa, Alina Liu, Dalit Steinbrecher, Eric Kalb, Jenny Wang, Natalie Fajardo, Sihan Zhang, Sumi Lee

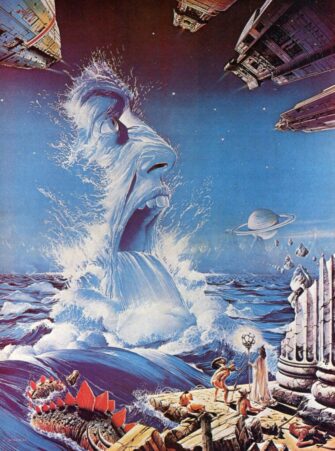

A previous related project done by Kevin: an abstract narrative reflecting on our relationship with and complicity in nature, industrialization, and our general ecological surroundings. It’s 3:30 min and please watch with webcam and sound on https://icarusfilm.herokuapp.com/

THESIS

The modern era brings us a global war on the environment — where humans, and more importantly corporations, act as parasites on this spaceship we call Earth, and the burden lies on art to harmonize technology, society, and culture with nature.

THE PARASITE, CAPITALISM

The United States is a frontrunner of a western, capitalist society, and is a worthwhile character in a conversation about capitalism. In 2009, the US Supreme Court received arguments whether or not corporations are citizens. The decision, delivered in early 2010, stated that corporations were eligible to receive rights from the Constitution. In this particular case, the ruling declared that corporations can receive First Amendment rights and freedom of speech (link). With no legal distinction between humans and corporations, do we lump ourselves together with the corporate collective? When an individual fails to recycle a single cardboard box, does that equate a corporation failing the same act on a tenfold-scale? The line is hard to draw, and we continue to rely on the Earth for a supply of resources that only appear endless. We need to close the loop on production. With the rise of global warming, the worldwide extinction of ecological habitats, with an increasing population and overall waste production, the future looks grim if we continue on this path.

On a global scale, even COVID-19 can be directly attributed to fiddling with the environment (link). Let’s talk about cell phones. They are made from a coltan, a mineral that is ultimately refined into tantalum, which is found in most, if not every, technological device. Any cell phone or computer owners are customers for this extremely rare mineral, which makes them (us) responsible for the miners of coltan. These miners may eat bushmeat while mining, and could come into contact with any new virus that might use the bushmeat as hosts (link). Consumerism, and an evolving society that relies on technology to function, brought us COVID and will bring future viruses. Unless we can mitigate our endless extraction of resources from the earth, and close the loop of resource gathering and waste production, we cannot find any harmony.

LIVING SYMBIOTICALLY AS A CULTURE

Although gloom and doom is pervasive, there are steps that can be taken to live symbiotically with the planet. Firstly, a cultural shift is required. Globally, we need to shift the conversation towards one that is more beneficial for the planet. Western socialist and eastern cultures focus more on the collective wellbeing, whereas western capitalist countries focus on the individual wellbeing of each person. The problem with the individualistic mentality is one that prioritizes greed. In a social aspect, individualist cultures are for their own gain. Additionally, due to supply chain and global resource gathering, individualism and capitalism are responsible for issues worldwide. For instance, in India where the start of the production line begins, worker compensation is extremely low for the amount of money that the product is retailed for (link). Workers make pennies for the hundreds of dollars items are sold for. All as a result of capitalism and corporate greed.

However, we can look at a smaller scale to find examples to shift the global conversation. Finland and Sweden, countries that are predominantly socialist, are an excellent example. They have the highest happiness index in the world (link). Prioritizing the wellbeing of the collective is inherent to their culture, and reflects in their policy-making process. We can also look at the Indigineous people of America, caring for the wellbeing of the earth and ensuring balance between humans and their surrounding environment. Creating a modern sustainable means of life will be extremely challenging, but it starts with a cultural shift to thinking about “we” and “us”.

VISIONARIES

Several attempts have been made to create the city of the future which can simultaneously fulfill the needs of both the community and the individual. Notable among them is EPCOT, the Disney theme park, originally conceived as a community 20,000 strong, and would be home to the staff of the yet to be built Walt Disney World. The Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow would have been a working city that tested new city planning concepts, technology, and materials, but the project was ultimately abandoned when Walt Disney died. Years later it would be reconceived as a theme park and would open in 1982 with Future World, and corporately sponsored attractions related to the future of Energy, Agriculture, Transportation, Space, Imagination. Maintaining a vision of the future ahead of our present proved difficult, and a theme park without thrill rides saw declining attendance, loss of sponsors and the eventual demolition of what remained of Walt’s vision. The icon of EPCOT, the large silver geodesic sphere is named “Spaceship Earth,” a term popularized by architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller. A few years earlier, Fuller worked on a project similar to Walt Disney’s original vision of EPCOT. A recent article in The New Yorker (link) documents the hope of the “Skyrise for Harlem,” a concept initiated by Black feminist writer and activist June Jordan in 1964, a gift to the community she loved in response to killing of a Black teenager by a white police officer. The concept was published in Esquire, redubbed “Instant Slum Clearance” by editors, a title antithetical to its original positive inspiration of rebirth of a community in decline (rather than the demolition of one). Nothing ever came of the project. These two projects share many things in common, key amongst them is the reason why they never happened: large change requires more than one visionary… many more. Zurkow spoke of Donella Meadows Iceberg Model “which depicts how what is under the surface is progressively more difficult to change, but not impossible, it requires increasing leverage – meaning in part analysis, time, and numbers of people with conviction.” The societal changes necessary for immediate course correction will be the only effective solution. Individuals can enact change, but it can only be achieved as a group.

SOLUTIONS

Much of our lives are ruled by “necrocacy,” a term used by Zurkow, which means “a government that still operates under the rules of a dead former leader.” Most of the rules, traditions, and conventions that control our daily lives were drafted by people who are dead, not just recently dead, but long dead. Some of these people have been dead for centuries, but despite more advanced awareness of science and technology, and evolved ethical practices, change is difficult and will require the efforts of a larger movement.

Fossil fuels are an example of something that we rely on, despite knowing the negative consequences of both harvesting and using it (and having more future-conscious alternatives). The infrastructure is already in place for us to rely on fossil fuels and the government is in the pocket of the oil companies, both factors that make the systemic adaptation necessary for a healthier planet near impossible.

The fate of our cities is in question at the moment for multiple reasons, the first is tied directly to fossil fuels and global warming: sea level rise. Fortunately/Unfortunately the rising sea levels do not care what color your state is on an electoral map. Studies have shown that several US cities will be at least partially underwater by the year 2100 (link). That will be in the lifetime of our children and/or grandchildren. The cities include New York, Boston, Miami, New Orleans, Houston, and Charleston. In “The Ecological Thought,” Timothy Norton recounts a story about the inhabitants of a Scottish village complaining that the turbines of a wind farm spoil their view. He questions whether they would rather have a pipeline. Residents of Lakewood, Colorado had similar sentiments regarding the installation of a solar array that would not look “natural.” Our wasteful needs have put us in this position and yet we still prioritize aesthetics over practicality. There is a certain amount of justice when erosion claims a mansion precariously built on the edge of a cliff.

Another reason for change in our cities is the exodus of their residents. Recently released census data has shown that population growth in major US cities had stagnated and been on the decline, even before the pandemic (link). The migration of New York City residents to the suburbs and summer rentals for the season may be more permanent than original estimates. With the pandemic expected to last well into 2021, and the ability of many to work remotely, residents of US cities may settle into permanent living arrangements elsewhere. Companies like REI sold off its newly built headquarters, and Facebook bought the site.

Does this mean the death of the big city (New York especially)? Although it is hard to predict, some have proposed that this exodus will drive down rent, allowing a more sustainable lifestyle for young professionals and artists, and revitalize culture created by young people in our cities. This is a possibility, but would require rent to be driven down to a reasonable level, and kept there. The opposing argument to this theory is that young artists have found outlets and communities through social media, and that the culture of young people has become geographically decentralized. The coasts no longer need to be the only hubs for media and the arts. Despite the numerous evils of social media, it has prioritized art and democratized culture, allowing demographics left voiceless in previous generations to have a platform of expression.

CONCLUSION

As parasites on earth, we must change to keep our host healthy enough to sustain us. This will require a tectonic shift in priorities in order to save both ourselves and our global neighbors.